There’s a general feeling, isn’t there, in your core, if you look at pornography, that this isn’t the best thing for me to do. (Russell Brand) Every culture uses analogies, metaphors, and figures of speech to convey truth and make it easier to remember. Imagery also enhances the appeal of abstract ideas that might otherwise be bland. Imagine a website with text and no images. It is unlikely to garner much interest, no matter how great the quality of the content.

The History of Moonshine

If you live in the US, you’re probably familiar with the name. Moonshine, technically speaking, denotes very strong alcohol (typically 40% to 80% alcohol by volume) that was traditionally made or distributed illegally. The term gained popularity in the US during the “Era of Prohibition” (1920-1933) when alcohol was criminalized. People who broke the law and distilled alcohol typically did so at night to avoid discovery. They were called “Moonshiners,” and their product was called “Moonshine.” Today alcohol companies have adopted the term and it has become synonymous with very strong alcohol of any kind.

Moonshine is strong to the smell and bitter to the taste. The body knows that it is extremely powerful (and dangerous). Consuming enough moonshine can lead to extreme side effects, the most radical of which is death by alcohol poisoning.

The History of Fentanyl

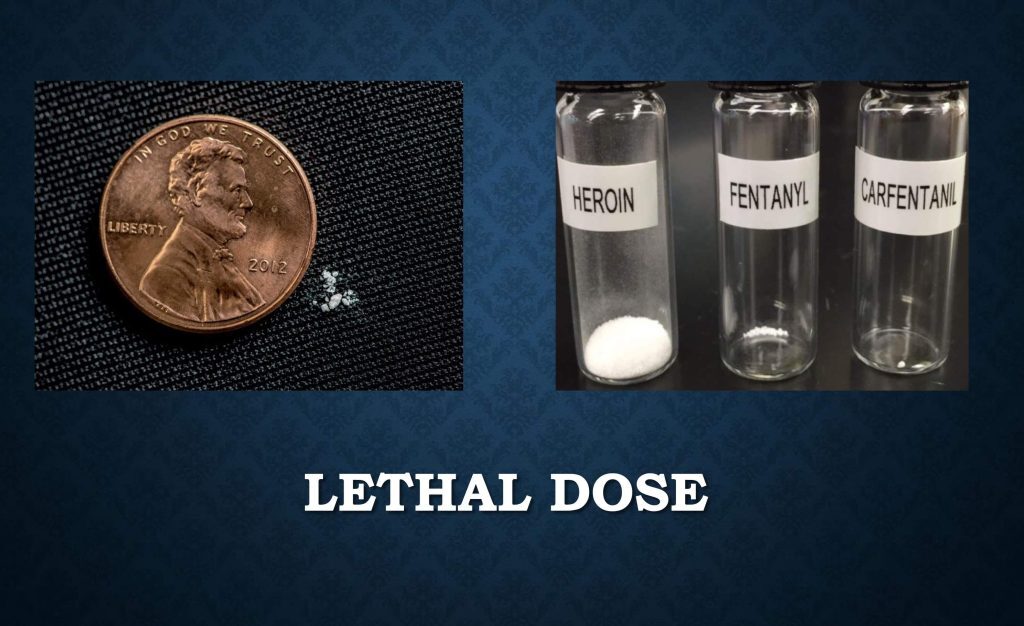

Fentanyl, on the other hand, l is a potent synthetic opioid that was created in the 1960s as an analgesic (pain-killing agent) by the company Janssen Pharmaceutica. Fentanyl is ~100 times more powerful than morphine and ~50 times more powerful than heroin. In 2019, fentanyl overdose became the leading cause of death in the US among people aged 18-45, (overtaking suicide).

Due to fentanyl being so cheap and powerful, many drug dealers in the US lace other substances with it (cocaine, heroin, ecstasy, etc.). The process of lacing a drug with another substance is called “cutting.” Cutting a drug increases its weight, making it more cost-efficient, and potentiates it, which can increase demand. This dynamic has led to uncertain outcomes where people don’t really know what’s in the street drugs they’re consuming. Since a miniscule amount of fentanyl can kill you, many people who are not suicidal, and have no desire to consume a drug so strong, wind up dying due to accidental overdose.

Fentanyl is eminently dangerous precisely because there are no warning signs. Unlike with moonshine, there’s no bitter smell or taste alerting the user to potential danger. What looks like an innocuous powder—or cannot be seen at all—is the very thing that kills you.

The prudent sees danger and hides himself, but the simple go on and suffer for it.

Proverbs 22:3

A Metaphor For The Conscience

Our consciences are designed as a defense mechanism against danger. The uncomfortable feelings they produce are supposed to give us pause and prompt us to think twice in advance of an action. In this sense, consciences function similarly to the pain of a muscle pull, the discomfort of being out in the frigid cold, and the bitter, unpleasant sensation we get when we smell or consume strong alcohol.

The more we ignore conscience, the weaker it gets. There are people whose consciences have become “seared” due to repeat disregard over time or some other serious psychological disorder. The sad truth is that these people are no safer for it. If they engage in unethical activities, they face the same consequences as everybody else. The only difference is they are caught off-guard (like fentanyl users), and unable to adapt themselves accordingly. Consequences aren’t just physical. They are mental, emotional, and spiritual, where the ravages can be equally, if not more, devastating.

After we watch pornography, we often want the consequences to go away as fast as possible. However, these provide valuable insight that can guide and grow us in the future. Viewed through this lens, consequences are a blessing for which to be grateful, rather than an after-effect merely to be dreaded.

Conscience, in sum, is an alarm system that serves to protect our interests and those of our neighbors. We do well to heed its advice.

For more, see the complete archive of articles on integrity.